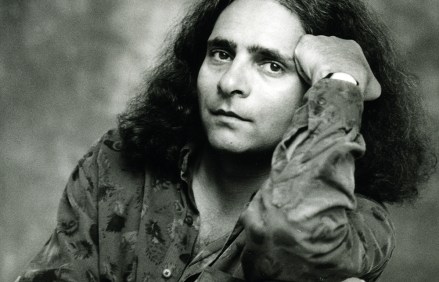

Hanif Kureishi – portrait of the artist as a young man

If any novelist, playwright or screenwriter of the past 40 years could be called ‘a writer of consequence’, to use the literary agent Andrew Wylie’s term, it would be Hanif Kureishi. While not shifting units on the scale of his near contemporaries Ian McEwan, Martin Amis and Salman Rushdie, Kureishi’s cultural influence – through his explorations of race, class and sexuality in novels such as The Buddha of Suburbia and films like My Beautiful Laundrette – is inestimable. In this first major biography, Ruvani Ranasinha tracks Kureishi’s progress from his birth in Bromley in 1954 to a Pakistani father and English mother, through his glittering, always provocative career, to the