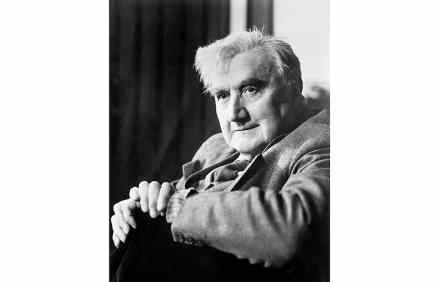

Vaughan Williams’s genius is now beyond dispute

Classical music plays hell with people’s posthumous reputations, as any admirer of the works of Ralph Vaughan Williams will tell you. In 1972, on the centenary of his birth, ample respects were shown. Not only were there special concerts of his music but the Post Office, which is now more focused on commemorating gay pride, issued a stamp. Since the composer’s death in 1958 he and his works had gone into an eclipse, not least because of the atonalists who controlled the Third Programme and many of our concert halls. These were people who believed the British music-loving public should be fed on a diet of what Kathleen Ferrier called