How much does Britain still ‘love’ the NHS?

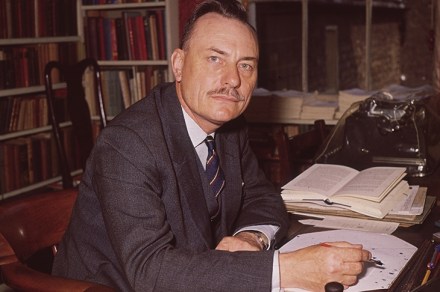

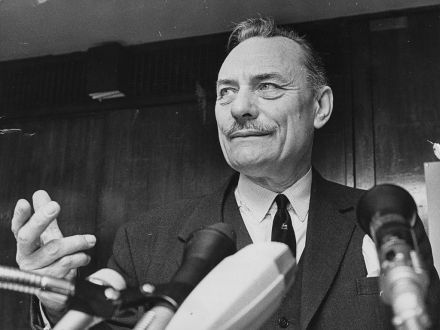

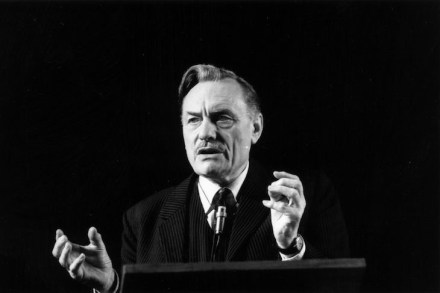

‘Of course I support the NHS. Everybody supports the NHS, or says they do,’ poked the comedian Frankie Boyle in one of the many campaigns promoting the health service. To admit you don’t believe in this national institution is as taboo as not caring about Britishness, about goodness, about people. The public is keen to find evidence for this collective belief. Nigel Lawson famously said that ‘the NHS is the closest thing the English have to a national religion’ – words which tend to be heard as praise. But his comment was laced with criticism. He continued, ‘with those who practise in it regarding themselves as a priesthood. This made