Could I find love at the British Museum?

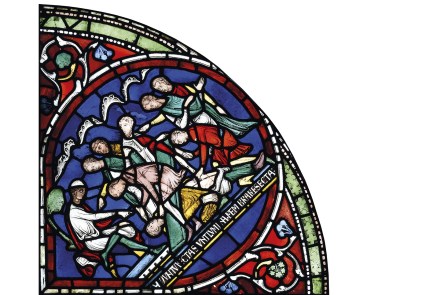

Mirabile dictu, as we Latin lovers like to say. In other words, wonderful news! Attractive women have fallen for ancient Rome – and for classicists. Well, that’s what the British Museum thought when it cooked up its advertising campaign for its new show, Legion: Life in the Roman Army, about Roman legionaries. The Museum put up a controversial social media post, promoting the exhibition as an opportunity for single women to find single men. I spotted a lissom blonde in green T-shirt and tie-dye trousers. We fell in step as we approached the gift shop The post read: ‘Girlies, if you’re single and looking for a man, this is your sign