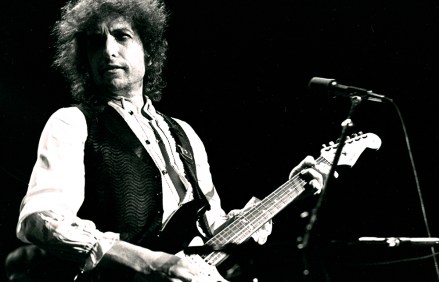

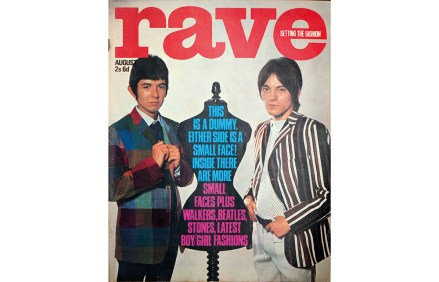

The data-spew about Bob Dylan never ends

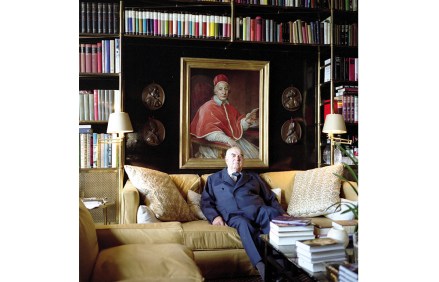

When it comes to Bob Dylan, Clinton Heylin is The Man Who Knows Too Much. Since publishing his first biography, 1991’s Behind the Shades, he has become the world’s most committed Dylanologist, doggedly untwining the facts from the artist’s self-serving fictions. When he describes Dylan’s wildly unreliable 2004 memoir Chronicles: Volume One as ‘all a put-on… all a lie’, he has the receipts. As he never tires of pointing out, scholars and diehards are in his debt, but amassing data from sessions, setlists and now 130 boxes of Dylan’s formerly private papers is not the same as telling a good story. For someone innocently hoping to understand one of the