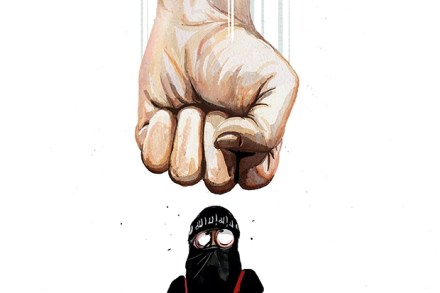

Afghanistan’s new agony

Amid all the chaos in the Middle East, the breakdown of borders and states, a new threat is fast emerging. The key strategic bulwark to stabilise the region is a strong Afghanistan. But after 15 years of occupation by western troops and a trillion dollars spent, it now appears to be going the way of the Levant. A weak government in Kabul has proved unable to forge a political consensus. The Taleban is resurgent, while other similar groups control much of the Afghan country-side. And this — with the potential spread factor of Isis — means that Afghanistan is probably worse off today than when foreign forces intervened in 2001.