Gender neutrality and the war on women’s literature

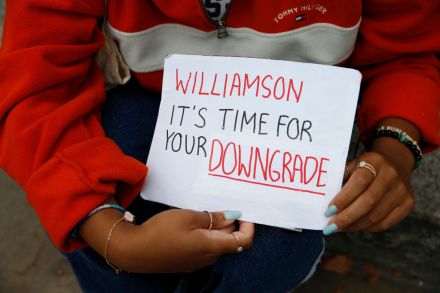

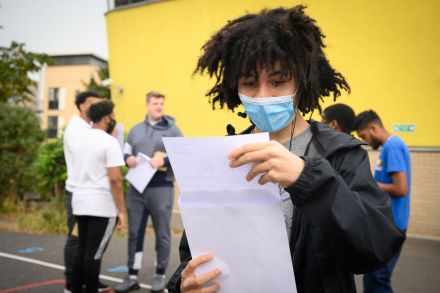

Education has become embroiled in a culture war and rather than extricating itself politely, it just keeps digging. What gets taught has long been subject to debate: move beyond the basics and you rapidly head into dangerous terrain (although, look hard enough, and you will find those prepared to argue that even maths and spelling are racist). Now it’s not just taught content but the name of modules that is under the woke microscope. One of the UK’s leading exam boards, OCR, has proposed renaming the ‘Women in Literature’ section of its A level English courses. It is taking votes on new titles: ‘gender in literature’ or ‘representing gender’. But